“This is a destroyed city,” Mihai told me on the drive into town.

Not really, I thought to myself. Not razed, not utterly crumbling, not polluted beyond repair. I peered at Bucharest with jet lag eyes, and liked it. We threaded through a forest park, along lively boulevards, around several gigantic chaotic roundabouts. Paint peeled from strange villas, stray dogs peeked out from alleys, plastic bags hung from street trees.

I liked the little hotel, which was in an old house recently renovated. Mihai said it seemed fake and cheap, but he paid for my room anyway and departed. My luggage had decided to explore the tarmac at Charles de Gaulle, so I went alone upstairs, sat on my bed for a moment, opened the curtains, thrummed my hands on the windowsill. There was a big bathtub made of translucent plastic in the middle of the room. My view looked out over the hotel’s driveway, where a few older men were standing around smoking cigarettes, paused while tiling a small patio.

When Michael Jackson came to Bucharest in 1992, he allegedly strode onto stage and screamed, “Hello Budapest!”

As I had a free day on my hands before an evening screening, I’d followed a friend’s advice and booked a tour with a little company named “Interesting Times Tours.” Checking my email, I saw that my guide, Robert, had sent a picture of himself and instructions to meet him in front of the KFC near the Piata Romana.

The day promised thick heat, but the morning was cool as I wandered the mile or so from my little hotel. I passed the old US embassy, a striking old mansion now overgrown with weeds; apparently the new embassy was more of a fortress on the outskirts of town. Romanian merchants were setting up tables for a craft market near a school. Bored security guards smoked cigarettes here and there.

Robert, 25, wore dark sunglasses and a small backpack. Two other tour members – ah, a member of a tour is a tourist! – stood at the ready, one a Romanian woman who said little, the other a Chilean industrial designer getting her PhD in Sweden.

The theme of the day’s tour was street art, but we spent the first hour generally wandering around looking at old buildings that Robert suggeted had been improperly restored. Apart from a few ancient churches, the oldest buildings in Bucharest seemed to be grand 19th century houses built by wealthy families who fled when the communists took over in the 1950s. Under communism, the houses had fallen into disrepair, and only a smattering had been fixed up—mostly by lawyers, foreign embassies and the like. Others allegedly host squatters, Roma families, or cats.

Painters – I mean, spray painters – had taken it upon themselves to spruce up the many crumbling walls of Bucharest. Robert knew most of these artists by name, or pen name, and we spent a few hours standing around on sidewalks, heads cocked like museum-goers, sweating in the rising heat.

I felt ill-equipped, as a novice street art assessor, to assess the quality of what we saw; there were some beauties, to be sure, and not too much stuff that could fairly be called crap. Which, I learned later, is the Romanian word for carp.

At some point, near an art supply store where Robert said he and his friends used to shoplift in his art school days, we hooked a left into a shadowy concrete structure. Someone had curated a parking garage, yielding a kind of museum of street art where you spiral up a ramp – Guggenheim-style, but square – and soak up the offerings. It’s not open to the public because it’s still used as a parking garage; we paid for 1-hour of parking and stood on the slopes taking pictures of crumbling walls near gleaming Mercedes.

At the end of the tour, which all in all was excellent, Robert dropped us off in a green park where at night hundreds of crows gathered. I wandered home by way of Piata Universitatii, where I stopped into an art gallery showcasing the work of a bearded man who sat near the door holding a plastic bag.

Mihai picked me up a few hours later to take me to the “projection” as he called it, but I first insisted we stop at the Romanian Geological Museum.

“Lots of rocks,” he said.

I nodded. “Lots of rocks.”

It had been closed to the public during the communist era, though the geologists rehauled the museum in the late 1970s, probably to keep things up to date after the plate tectonics revolution. Still they hadn’t opened it, because any museum opening would have necessitated a big ribbon cutting with Romania’s dictator, and this evidently seemed unappealing. Eventually they’d shot the dictator – the revolutionaries, not the geologists, although there’s always an amateur rock collector in a group of revolutionaries – and the museum reopened.

We had the place to ourselves. I liked seeing scientific names in a foreign language. I liked the dioramas of volcanic activity, the cutaways showing the Earth’s core, the rows and rows of sparkling and strange and humble stones together under glass. Upstairs were drawings of dinosaurs made by schoolchildren.

When we’d had our fill of rocks, I bought some stamps with deer on them at the museum store, where two ladies were chainsmoking and watching the news on a tiny television.

Mihai and I jaywalked over to the enormous National Museum of the Romanian Peasant. There were big stone steps, cavernous halls filled with costumes, tools, grist mills, even an entire cabin. I prepared to take pictures of some bowls that had been tacked to a wall, and a museum guard appeared from the gloom and shook her finger at me. Mihai came to my defense, saying – I think – that we were guests of the museum director, here to show a film. She would not be cowed, and I picked up the familiar intonation of “I don’t make the rules, I’m just doing my job.”

I loathe being told not to take pictures of bowls in peasant museums, so here is a picture I took of bowls in a peasant museum:

During the communist era, the museum had been used to showcase the great heroes of communism. Most of the busts and paintings had presumably been destroyed after the 1989 revolution, but in the basement Mihai and I found a few rooms packed with icons of Lenin and Stalin. Along one wall were dozens of small painted sickles-and-hammers.

Mihai stood for a while at one end of the room, reading a newspaper from the 1950s that heralded the era of collectivization — when peasants were rounded up, entire villages shuttered, and massive new farms forcibly created. I approached to have a look, and Mihai turned suddenly towards me, saying with a chopping motion, “I cut your penis off, then I give it to you and say, this is yours, use it. That’s collectivization.”

Seven people showed up for the film screening, which was in a big beautiful lecture hall near a flea market where old ladies sold Slavic clothing and raspberry soda. While the movie played I drank a raspberry soda, rang Amanda, watched three cats lounge around some graves. Mihai told me later that the communists bulldozed graveyards fairly indiscriminately, so someone from the peasant museum had rescued a few headstones from the 19th century and stuck them in the shrubbery outside the back door.

The following morning was the tour I’d intended to sign up for: Beautiful Decay. A chance to wander some abandoned or forgotten buildings around Bucharest. I joined Robert again in front of the KFC, and this time there were four of us tagging along: me, a professor from Texas who studies the history of time, a super-friendly furniture maker from El Salvador, and an itinerant Swiss woman on her way back from Georgia (i.e., Georgia on the Black Sea) on her Vespa. She owns six motorcycles, is a former pastry chef, and avoids all high school reunions. Last year she trained to be a Skoda mechanic.

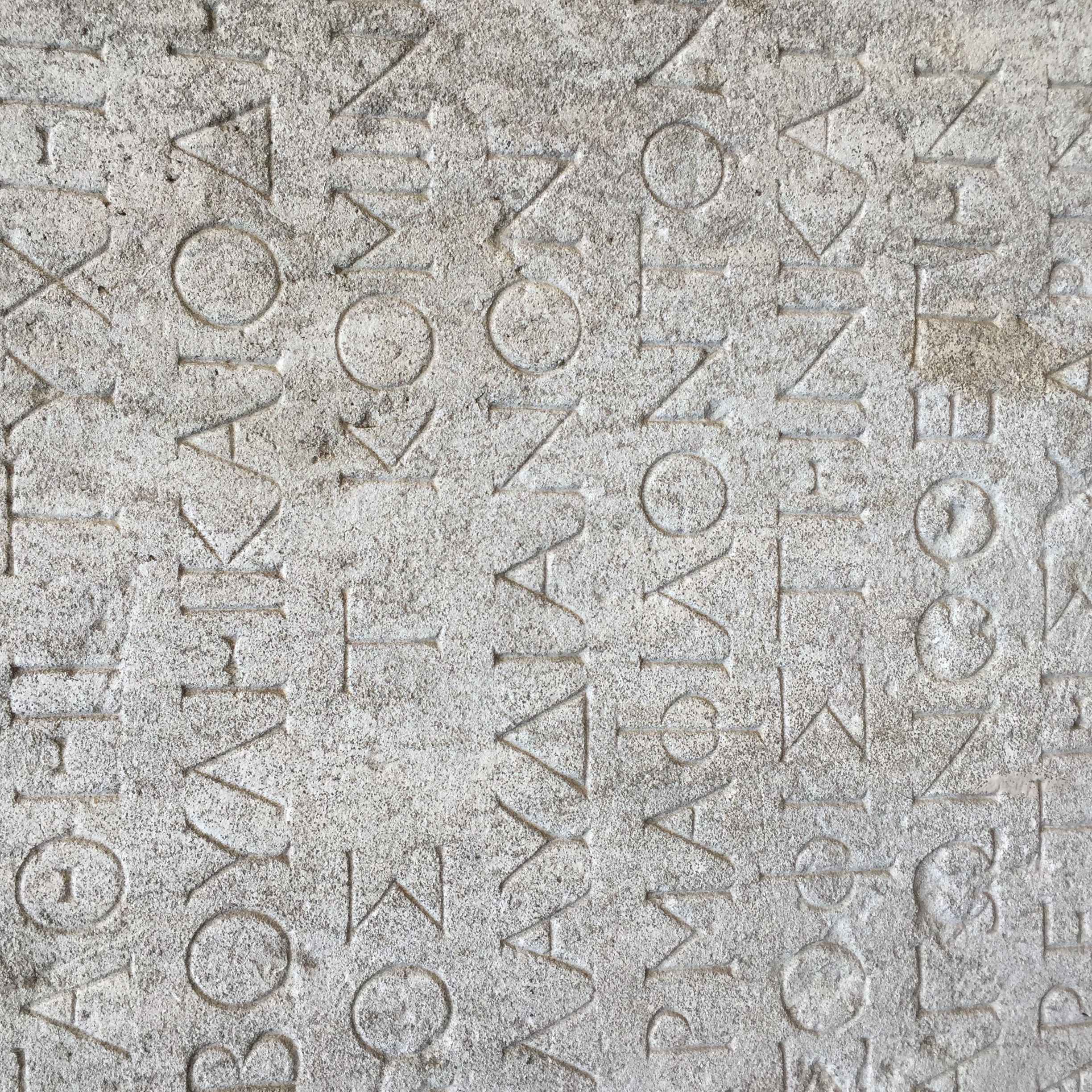

Our first stop was an old house that was occupied by archaeologists, though none were in sight, and the building seemed to be slowly descending into the Earth, as if the archaeologists were ensuring that future apprentices would have something to dig up. A security guard smoked cigarettes in a small room with a TV. In the back were piles and piles of stones with Greek lettering, apparently dating back to 100 BC, and a small shack where lived the security guard. I admired his cucumbers and tomatoes. Someone snapped a photo of his Citroen.

A circuitous wander through town and two brief bus rides took us to the contemporary art museum, in a small wing of the enormous palace the dictator had built for himself. We got a good view of the city, and I saw two stray dogs near a clay tennis court. In the stairwell, a street artist had sprayed his tag, subtitled “I finally got into a contemporary art museum.”

The subway ride to the outskirts of town took 15 minutes or so. The subway was spotless, easily the cleanest I’ve seen. Emerging into late afternoon sunlight, I smelled effluent and rot, but saw only a broad boulevard and rows of scrubby trees. We walked a few hundred yards and headed off the road towards a dozen or so crumbling structures. The Swiss motorcyclist found a plum tree and cut up a green one for us with her Swiss Army Knife, which she’d had to check at the door of the art museum.

I don’t know why I’d wanted to see ruins. They weren’t particularly old. Former munitions factories had been turned into fertilizer factories – swords to ploughshares! Same thing in the states — and then abandoned a few decades back. We ran into some guys shooting a music video, glumly hauling around stacks of drums – floor toms, tom toms, snare drums – and a few amps that weren’t going to get plugged into anything. Robert told us a lot of models come out here for photo shoots.

I took the pictures I’d imagined I would take: small plants sprouting from cracks in cement; holes in the ceiling for shafts of sun to slant through; rubble and glass and sand and sky.

Did this fulfill some expectation I had of a former communist country? Grey buildings? Check. Crumbling infrastructure? Check. Graffiti? Check. What the hell was I after, anyway. These buildings could have been anywhere, like my old neighborhood in Brooklyn near the Gowanus canal. What did my brother call it? Ruin porn? How fitting that some of the street artists had followed a geometric, vaguely sci-fi theme, as this would have been a great spot to play laser tag.

Well, whether you wander Rome or the outskirts of Bucharest, ruins do get you thinking about time passing, which is never a bad thing. I mean, it’s usually depressing, but a good dose of perspective helps stave off the mindless hustle of the iAge. As usual, I began wondering what future archaeologists or geologists might unearth from these old buildings. How long does spray paint last? Here’s a spot where rebar has left a strange spiral, that telltale fossil of the Anthropocene:

Robert needed to get back to Bucharest to record some sound for a documentary he was making about rural Satanists in Transylvania (“they do yoga, meditate, that sort of Satanism,” he had explained at lunch), so the four of us tourists decide to find a café. For dinner we had eggplant, pork in various incarnations, and a loaf of very dry bread. Four adolescent girls sat at an adjacent table drinking Mountain Dew and eating deep fried balls of cheese. Then we dispersed; the Swiss motorcyclist headed off to Bulgaria to find some maps she’d stashed there, and I headed back to my hotel with all my pictures of a city that time will never quite completely destroy.