In the harbor, some forty minutes from the tiny airport where our bags were unloaded into wide puddles on the empty tarmac, which alternately baked and soaked under the Bahamian summer haze that permeated all the dilapidated towns we drove through in a rickety green van stuffed to the gills with swim fins, Patagonia backpacks, camera gear, two famous surfers, a journalist with a recent article in Playboy and a twinkle in both eyes, one legendary body surfer, an environmental science student from California, several plastics activists, a representative from a water bottle company, a few local teachers, Simon my musician friend who would be running sound, and me — in the harbor we saw three nurse sharks.

They lounged in clear water near the marina restaurant, closed that day because the owner had been thrown from her car and killed. Nurse sharks are docile enough that you can swim with them, but I peered at them from afar, feeling somehow alien, pale—duly stunned after a long New England winter to find myself on a slender island in the Caribbean, boarding a three-masted schooner bound for the Bermuda Triangle.

The boat, or ship, let’s call it a vessel, was over a hundred feet long, with some thousands of feet of rope looped everywhere you turned, fresh wood decking, a spacious salon with a strapped-in piano, air conditioned state rooms, an ice-maker, an old ship’s clock, piping covered in boisterous beach party bumper stickers, a quiet captain, no cats. From the water, where the nurse sharks noodled around eating God knows what, you could see its name: Mystic.

We had a few days to acclimate to the humid land before thrusting ourselves out to sea, so we wandered over to the nearby Island School for a summit of Bahamian youths interested in environmental activism. I’d missed the beach cleanup, but we landed in time to attend a conch festival, where you drink rum, eat deep fried conch fritters and watch a fashion show featuring clothing fashioned from trash. A few shy teenagers wandered around with baggies of greens that they’d grown in the school’s hydroponics system. I caught up briefly with Jack, a musician friend who had invited me to come along on the expedition. He had brought along his guitar, as well as an underwater super-8mm camera, a throwback to his filmmaking days when he shot surf films. We chatted about our ideas for this short film - a journey through the plasticene ocean - before he wandered off to dance with his kids. Simon and I caught a lift back to the Mystic. Jupiter and Venus crept closer together in the sky.

The next day Simon and I filmed some initial interviews, drank multiple cups of coffee, discussed the grim possibility that there mightn’t be peanut butter available aboard the Mystic, and listened to a local band - the Rum Runners - while an afternoon storm rolled in. In the Bahamas, great stretches of turquoise sea tint the underside of clouds. It’s a planetary phenomenon I had not seen before, and one I failed to capture adequately on camera. It made me think of the buttercup flowers we’d hover beneath our chins as kids. “Do you like butter?” I do, and the light of turquoise seas.

Jack, the Malloy brothers, and Mark the bodysurfer decided that we should go find some waves before heading out to shoreless seas, so I suddenly found myself making a surfing film: here’s the shot of the boards getting loaded atop the old car; there’s the car rounding the bend as it approaches the beach; here we are on the beach saying things like “looks totally surfable.” Marcus Eriksen - the MacGyver-like scientist and co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute who would be leading our plastics expedition aboard the Mystic - brought along a mammoth board made entirely from old surfboard scraps and hundreds of plastic lighters collected from albatross corpses at Midway Island. Mark the bodysurfer - a living legend in Hawai’i and a retired lifeguard - found an odd foam mat to surf with. Off they went. Keith and Dan Malloy swam effortlessly; they’d already swum 4 miles that morning. Mark looked so comfortable in the water that you’d imagine him ill at ease on land, except that on land too, he’s a joy to be around, easily one of the most thoughtful people I’ve encountered in my travels. I stood on the shore with Simon and my wide-angle lenses until the surfers disappeared from view (the shore break was a quarter-mile out), and then we snorkeled and urinated in the shallow waters. Plastic littered the beach.

That evening, at the reopened marina restaurant, we sipped beers and dangled our feet above the green water, watching the nurse sharks. Jack ordered a strange green drink, which was made by mixing something yellow with blue curaçao. Simon brought up the mysterious matter of sharks’ reproductive systems, and we all looked at our plastic phones, which looked back at us blankly, far from any cell service.

In the morning Simon and I charged batteries and secured the gear in Pelican cases, anticipating rocky seas: at high tide the Mystic would launch. The crew gathered in their brown polo shirts - the Mystic is usually a boat chartered by rich people to sail the seas - and I was told that if the order was given to abandon ship, I would get into lifeboat #4. Simon and I took dramamine and drank more coffee. Hundreds of hermit crabs piddled around on the dock. Mark and the Malloys swam in the harbor.

To this day I don’t know whether we raised the sails because it was useful, or because it made people feel like we were sailing. But either way, with Eleuthera retreating into the rear of our polarized sunglasses, the sails went up. Our crew - a mix of plastics activists, company reps, students, and “high-profile water people” brought aboard to see firsthand the polluted ocean gyres - pitched in with some rope tugging and selfie-taking, and by the time Chef 1 and Chef 2 - the former from Boston, the latter from Birmingham - had trotted out an evening meal of lasagna, cornbread, and fresh salad, we were out of sight of land. The engines rumbled on.

Our path would take us through the deep waters of the Sargasso Sea, named for the myriad species of Sargassum that collect there, caught by the spiraling surface currents that made up the North Atlantic Gyre. Presumably, we would be sampling what else got caught in the gyre. I figured we’d see it right off the bat: massive piles of floating debris. The much ballyhooed plastic garbage patches.

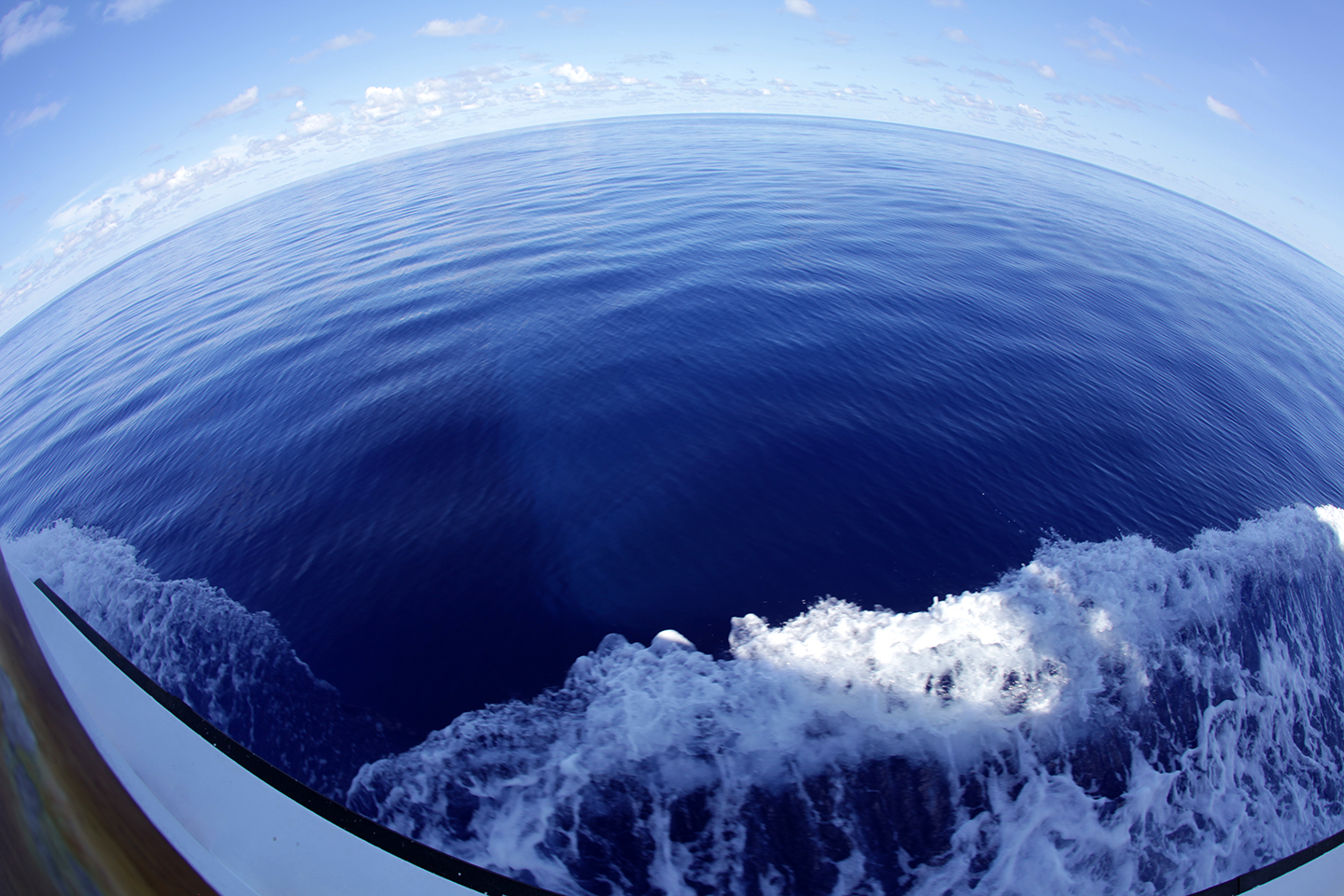

But this was clear blue water. So blue that I thought no one would believe the pictures I was taking. The color of the sky’s zenith on the crispest spring day. Fake blue. Neptune blue. And clear, clean, pure. No land no boats no garbage no nothing.

Then in went the trawl. Marcus had invented a variety of trawls— small nets attached to steel “mouths” that rode aside the ship and skimmed the surface of the sea. Watching it, we saw nothing but clear blue water sliding into the net, so there wasn’t much anticipation when we hauled the first trawl in after an hour. Marcus explained that we’d sampled an area equal to about two football fields, which I calculated to be 1/33,880,011,519th of the Earth’s ocean surface. In other words, a drop in the damn bucket.

And here’s what we found:

So you multiply that by 34 billion and you get a lot of plastic in the sea. Not big floating barges of trash but, in Marcus’ words, a smog in the sea. And these plastic bits, which are hydrophobic brethren to petrochemicals like DDT, accumulate toxins in the sea, and then get accumulated up the food chain, landing in the fish we eat, and in countless creatures that we do not. Marcus passed around a binder of recent scholarship on the effects of this plastic smog, and we listened to evening lectures by plastics activists until all of us found the phrase “single-use plastics” to be synonymous with, well, badness. But admittedly I found myself most disturbed not by the health effects of this plastic sea, but by what it did to my sense of the wilderness.

I’m not a sea guy. Not a water man like Jack or the Malloys. But, like Ishmael, every now and again I find myself drawn to the water. I don’t even have to go there, physically. What suffices is a landlocked landlubber’s daydream: in my mind's eye the vast blue sea, still wild and unknown, restores my sense of the mystery and boundlessness of this otherwise humdrum urban world. The ocean, like an outer space here on our own planet.

Put another way: it behooves the city dweller to imagine an untrammeled elsewhere. But as Marcus reminded us, there is no longer an “away.”

My camera eye liked the confetti of plastics splayed out in our filter trays - the same baskets used to steam buns in Chinese restaurants - but my inner eye reeled at the realization that we’d thoroughly stained the sea. For God’s sake, I thought, we’re in the middle of nowhere. This would be like landing on the moon and finding bits of Evian bottles and scraps of plastic bags. How did this get here?

You can’t trace a microplastic back to its source, not precisely anyway. But you can study the waste streams on Earth’s continents, and from there glean what you already knew anyway: we all put the plastic in the sea. Americans have comparatively strong waste management infrastructure, but each of us uses so much plastic that inevitably it leaks out; Marcus compares the sewer systems of major cities like New York to horizontal smoke stacks, belching our toilet and storm drain detritus straight out to sea. As his research vessels have neared the Statue of Liberty, he’s sieved unimaginable nonsense from the harbor waters — from tampon applicators to cigar tip wrappers. Add to that anything that blows from a landfill, or spills from a shipping crate, day after day, year after year. Abroad, many developing countries use less plastic per capita, but what they do use has a much higher chance of escaping lax waste management facilities — first to rivers, then downriver and out. Everything gets everywhere.

When it gets to the sea, plastic starts to break down. On beaches, the sun slashes at the plastic’s bonds. On the open sea, windy surf slices it into shards. A lot of it floats, bobbling around the surface until some creature gobbles it up, or until some microorganism colonizes it. This is called “fouling,” and if a bit of plastic lands enough algae, the erstwhile raft can sink. Marcus’ studies have indicated that a vast quantity of microplastics in the ocean are unseen; they have settled to the sea floor or soured the bellies of fish.

On our fourth day at sea, Marcus announced we’d be drinking wine that had been donated to the expedition. Metal cups were handed out, and as the sun set we sat amongst the trawling equipment and the stray strands of Sargassum, sipping some pretty darn decent vino, probably from California. Simon contributed a few tunes to the mix, Dan too, and Jack turned his Klean Kanteen into a slide. Andy Keller, the guy who started Chico Bags, dressed up as a plastic bag monster and generally trounced around on deck. As the stars popped out a few of us lay atop the salon, somehow avoiding the mizzen mast’s jaunty swings to and fro, and did our darndest to remember the constellations. The low-latitude skies are always a little disorienting for me, but once I can place my barn in Maine relative to Polaris (in this case, halfway into the sea off the port side of the bow), things start clicking into place.

Mercifully, there’s not a lot of plastic in the sky. But light pollution - the fog in the skies above urban areas - is a decent analogue for sea smog, the plastic fog of our five oceans. Like light pollution, plastic marine pollution is preventable, it’s lamentable, it’s a tragedy of the commons, but most of all it’s a design problem. With lights, you cap them, point them only where you need them. With plastics, you make things that biodegrade. Right?

You do other things too. You ban plastic bags, you eschew bottled water. But the general sense aboard the Mystic was that there’s only so much we can ask of consumers. Fair enough; there’s certainly plenty of evidence to suggest that we can’t bothered to reduce/reuse/recycle. So redesigning stuff from the start seems like the best way forward for the long term.

The crew announced that we were all eating too much and taking too many showers. To avoid running out of food and water, the ship would accelerate and reach port a day earlier. But first, some keen-eyed Mysticker had spotted a windrow of Sargassum. A large floating blanket of seaweed that host its own little ecosystem on the open sea. Sargassum is the genus. There are over 250 species. I have no idea which species we were encountering, but Marcus wanted to quietly approach in the Zodiac and see if we might find some wildlife in there. Or some plastic.

A few of us joined, including spearfisherwoman and free diver Kimi Werner from Hawai’i. We found a few creatures floating amidst the golden Sargassum, but for every critter we also found a bit of plastic — remnants of a bag, or some unidentifiable chunk that had been chewed on by fish or turtles. Kimi took one of my cameras down for a look from below:

Deep blue sea. Beautiful and terrifying. Swimming there, I felt the terror of the sublime, the irrational fear of being consumed from below, the irresistible urge to dive deep into that blue and break through to the other side. Okay, the resistible urge. I threw some Sargassum at Simon and climbed back into the Zodiac.

In a few days I’d be home, walking the terrestrial plastic world, and I needed to sit there for a minute in the boat and just pretend I was floating through the Earth’s last great wilderness, the ocean untouched and unknowable, like a great reservoir for all the metaphors we’ll ever need.